Urantia

| 2004 - 2006

The plane flies over the city preparing to land, we’re finally about to arrive. The night spreads out over the huge city that seems to have no limits, no beginning, no safe place to stop. A sea of lights, dreams and illusions. If anyone ever tried to define the city they made a mistake, I will not. The plane lands, we are in Mexico City, the most unclassifiable city in the world. Anything can happen here. Among a miasma of colors, of peaceful trees, of worn stones, I discovered a woman, María José Romero. She said she was a painter. We chatted, drank and laughed a bit. Later, I went to her workshop, a large place, uncluttered, without any pretention, a mirror unto itself. She has a table full of materials, pigments, brushes, bowls, fabric, pencils, charcoals, dust and fingerprints. It’s all there, and due to a strange inclination of the spirit when one enters such a place one immediately knows what kind of person they’re dealing with, what kind of artist stands before them. Without having seen a single painting, the stature of the painter can be perceived.

María José Romero pulls out paintings along with whispers, glances and smiles. She is a shy woman.

A workshop is where the real paintings are to be discovered, where you can see the bodies, the inside of the canvas, where everything is more intimate, more open. That’s where we can see failed attempts, vain efforts, clear desire, a shaky hand, where we can get an idea of the whole process of a work. A picture is never just a picture, a single state, that which any viewer can see in a gallery and for which the painter will be judged, often wrongly. It can be argued that that is all there is and this is certainly true. However, in painting, seeing means seeing beyond, if not there’s nothing to learn, enjoy, to make your own. A picture is a path unto itself, different states that occur over time, options selected without knowing if one is right or wrong. You trace a line here, another there, and when you think you’re close to the goal you grow unsatisfied, then you scratch, cover, erase, etc.

This can be repeated a thousand times or you can paint a picture in seconds at the first attempt. Anyway, as Edward Manet said: “Everything must be done quickly and without regret.” At least that is what should be communicated so that the painting has a positive effect on us.

María José has work that seems to have been made very quickly. But make no mistake, they bear the mark of time, clear days and sleepless nights, the passing of years in which we learn and become more subtle, nothing comes from nothing. At other times, María José offers us a more elaborate painting, with more elements, fuller, but while we contemplate it an idea emerges, a strong, clear intention, proving Manet’s phrase cited above. María José’s pictorial personality manifests itself in many ways.

While Maria Jose showed me her work and I became more curious about her painting. The idea that I would write the introduction to this exhibition came up and I gladly accepted, I felt I had the need to say something and this could be of interest to Mexicans. I am a foreigner, an old European, I live in a different climate, Greco-Roman, but I love Mexico, it fascinates me. Given the universality of all great art I think I can inspire many people to appreciate and enjoy this exhibition.

Contact definitely enlightens, enriches.

Painting should be viewed as directly as possible without too many obstacles to obscure it. Yet, I know this is not strictly possible, as one sees, feels and expresses themselves according to certain cultural forms. The Mediterranean, the old Europe to which I alluded in regards to myself, determines the content of my perception, extending it and at the same time limiting it. Everyone is who they are. Looking directly with one’s own eyes without remedy involves everything that I say. Nothing is innocent, the innocent eye does not exist. Everything is fixed in time and in space, we only get from it what we choose according to our own taste, which is to say, our character.

Leonardo and Botticelli met in Florence in the late 15th century and they shared many things but their painting was very different because their interests and character were, too. Giotto’s contemporaries said that his figures were so real they only lacked speech, but to us although they might seem magnificent they also seem very stylized, far from any naturalism.

Every era, every place, has its own way of being, breathing, walking. We all belong to a tradition, nothing is free. As Eugeni d’Ors said: “Everything that is not tradition is plagiarism”.

Earlier I referred to the universality of all great art, and this is definitely its best condition. But, by the same token, it follows that this universality can’t exist without the local, that is, that which we all share, by means of which we all understand each other, that which moves all of us, has a concrete and specific origin, one very difficult to access.

We are uplifted by an Ogata Karim painting, a Japanese artist of the 18th century, without ever having been to China or Japan, without knowing anything of the garden where it came from. The screen, the dried flower, the still vase, are forever in movement.

We have given the exhibition of María José the title Carmina, a Latin word which when transposed into our language has a broad definition which can mean songs, compositions.

I think the title is very suggestive for her paintings are songs full of different forms and intentions, whose somewhat veiled main theme is painting itself.

The Carmina paintings offer an unusual variety, each has something specifically individual, which shows the work that went into its conception and realization. This painter does not fall into the reflex mechanism of clueless, unreasonable repetition of everything that has already obtained some commercial success, which is the death of art. She also does not fall into the opposite but equally useless trap of changing styles and subjects aimlessly, without the slightest integrity, demonstrating only a desperate inner poverty.

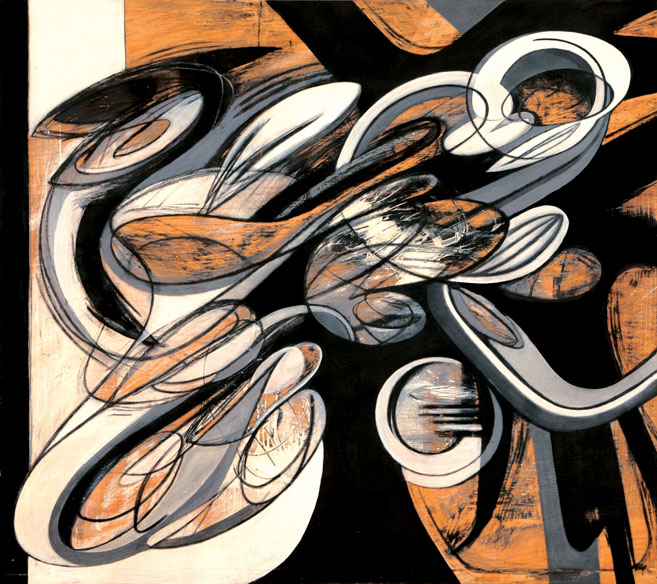

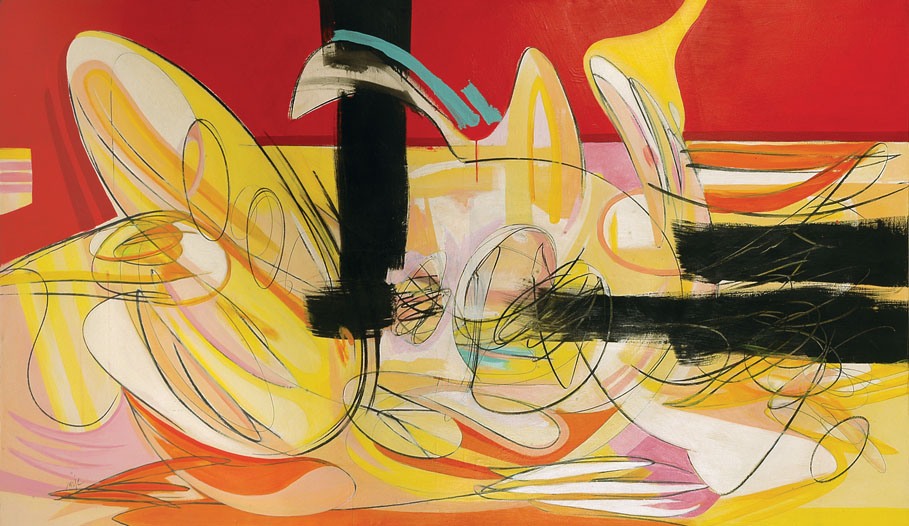

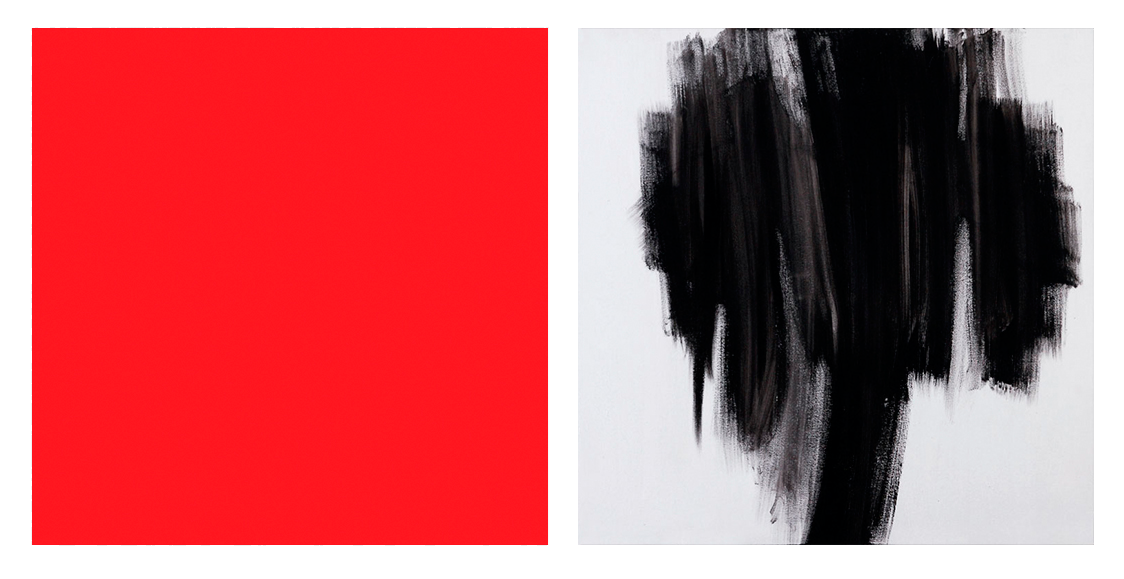

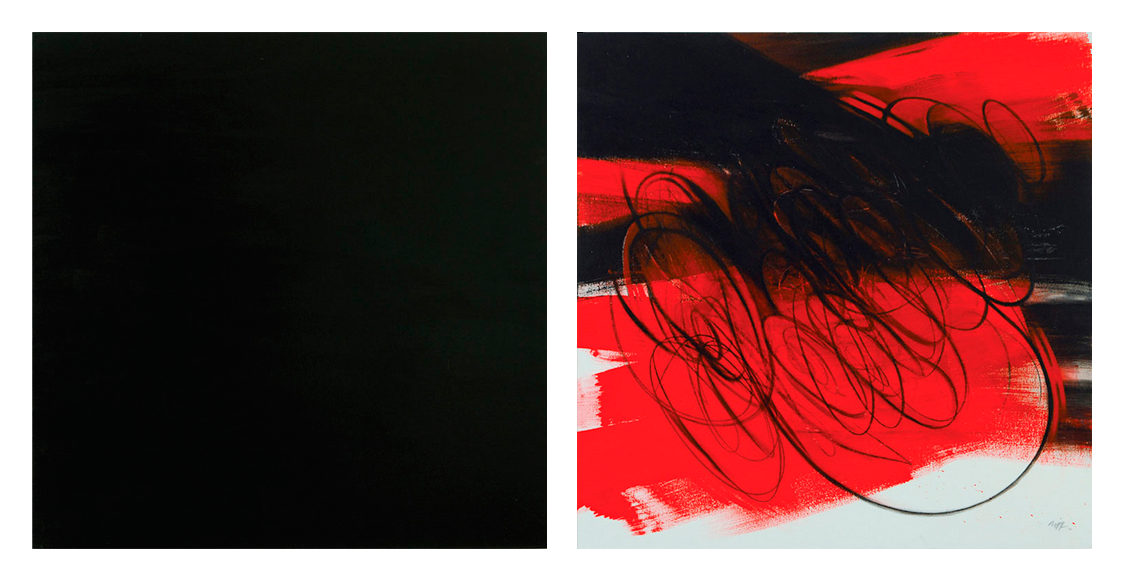

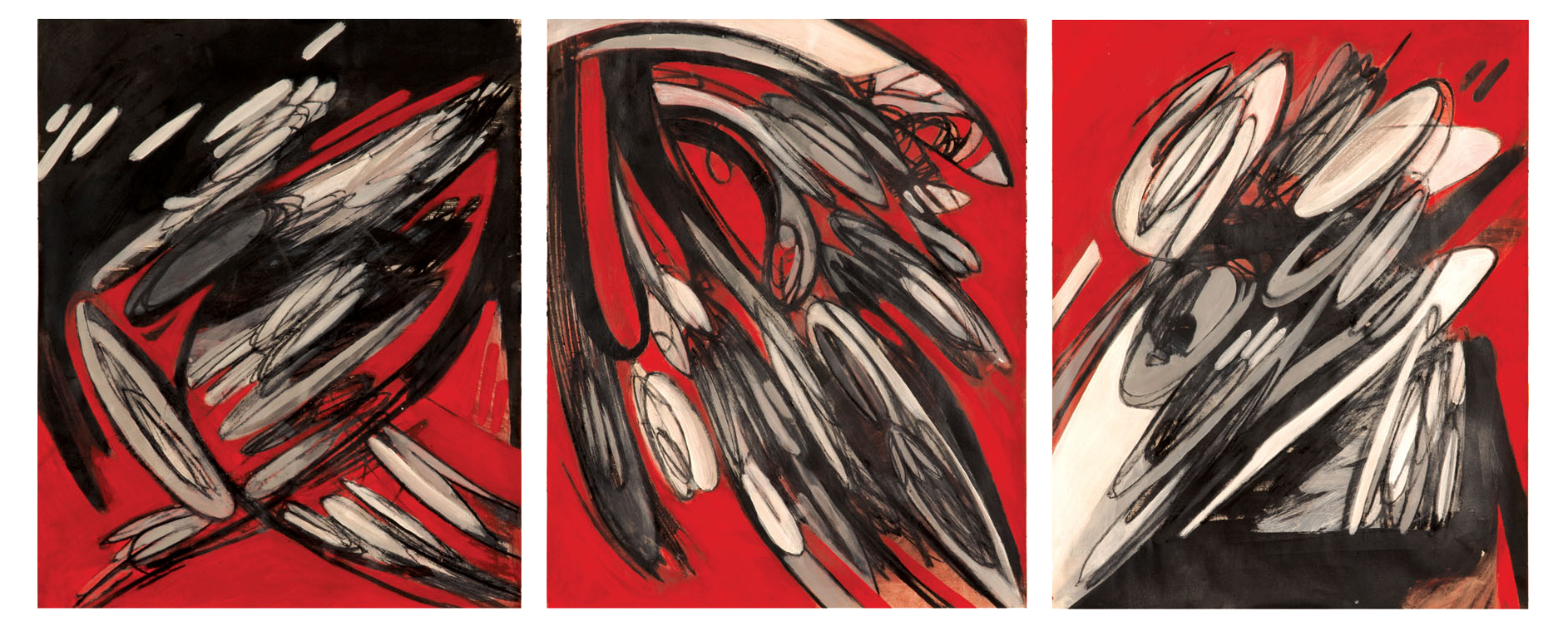

In the present exhibition we enjoy her different ways of painting, the language is serious and rich in solutions that complements the work. The main technique presents rigorous brushstrokes in usually clearly defined areas. These spaces interpenetrate, play and are interspersed ad infinitum. Paintings so gestural and dynamic they seem to dance. By their pure, bright colors, as well as for their freedom of movement, it is almost an attack on form, which might remind us of Francis Bacon and the most linear aspects of Hans Hartung.

Although the work of María José, as anyone can see, is stylistically very different, with no reference to figurative work, at least directly, nor like Bacon do they predispose the viewer to a pessimistic or somewhat tormented experience. The paintings of María José, despite the fact they always reproduce the pain, like all true art of struggle, passion, tremors, possesses a vital character that inspires joy. Contained within a kind of meditation that completes and deepens the work. The difference between María José and Hartung is that her work is more calculating, colder, and as I’ve said, María José has a vital, intuitive, fresh nature.

We could find many similarities between her painting and 20th century European painting but I think it’s not worth mentioning, as everyone will quietly encounter this. The important thing is to realize that this is a totally original painting, authentic, born of its own Being. Sure, one painting resembles and owes more to another painting than to nature, the real inspiration from which it supposedly arises. This is the weight of tradition, which I have noted above by quoting Eugeni d’Ors, which is what the history of art is all about.

We have in this exhibition a work, a polyptych entitled Attempts to Fly, which to me has a unique strength and beauty, the pearl of the paintings presented here. This painting exists for the brushstrokes that fill the pictorial space, taking possession of it and which no longer act like those in the other paintings, within well-defined areas of pure color, here the only limit is the canvas itself. The background color, a neutral grayish ocher, acts as a catapult, giving all the privilege to the black lines that move and dance, no longer in space but space itself.

Little can be said that you will not see as the appraisal and appreciation of a painting is subjective, but there is what might be called a very strong presence, an emotion that can move anyone.

I don’t want to ramble on or get too heavy. What brings us here is the work of María José and not my words. Words are often traps, prisons of meaning. I have tried to make my words a path that you can take towards the heart of this work.

Mexico City is a meeting place for me, not between two traditions but between European sensibility, me as a spectator and an American sensibility embodied in the work of this great artist.

Our traditions, after all, are similar, for in its colonial period Mexico connected with the Greco-Roman past and Europe connects with the pre-Columbian past by means of the surrealism of artists such as Roberto Matta or European painters who have spent long periods in Latin America, such as Shum or Sucre, little known to the general public but a decisive influence on men like Antoni Tápies, Guinovart and many others.

I would like María José’s painting to be seen as an amalgamation of traditions, productions, of comings and goings. All great art sets the trends of its time and, let’s not forget, it often also opposes and confronts them. Let’s celebrate the success of this exhibition as our success, too.

Miquel Arman Lladó

Painter and Restorer of Artworks of the University of Barcelona

Mexico City, 2006